Robert Rauschenberg

Posted by Fabio 14 May 2010

Born in Port Arthur, Texas in 1925, Robert Rauschenberg imagined himself first as a minister and later as a pharmacist. It wasn’t until 1947, while in the U.S. Marines that he discovered his aptitude for drawing and his interest in the artistic representation of everyday objects and people.

After leaving the Marines he studied art in Paris on the G.I. Bill, but quickly became disenchanted with the European art scene. After less than a year he moved to North Carolina, where the country’s most visionary artists and thinkers, such as Joseph Albers and Buckminster Fuller, were teaching at Black Mountain College. There, with artists such as dancer Merce Cunningham and musician John Cage, Rauschenberg began what was to be an artistic revolution. Soon, North Carolina country life began to seem small and he left for New York to make it as a painter. There, amidst the chaos and excitement of city life Rauschenberg realized the full extent of what he could bring to painting.

Rauschenberg’s enthusiasm for popular culture and his rejection of the angst and seriousness of the Abstract Expressionists led him to search for a new way of painting. He found his signature mode by embracing materials traditionally outside of the artist’s reach. He would cover a canvas with house paint, or ink the wheel of a car and run it over paper to create a drawing, while demonstrating rigor and concern for formal painting. By 1958, at the time of his first solo exhibition at the Leo Castelli Gallery, his work had moved from abstract painting to drawings like “Erased De Kooning” (1953) (which was exactly as it sounds) to what he termed “combines.” These combines (meant to express both the finding and forming of combinations in three-dimensional collage) cemented his place in art history.

Rauschenberg’s enthusiasm for popular culture and his rejection of the angst and seriousness of the Abstract Expressionists led him to search for a new way of painting. He found his signature mode by embracing materials traditionally outside of the artist’s reach. He would cover a canvas with house paint, or ink the wheel of a car and run it over paper to create a drawing, while demonstrating rigor and concern for formal painting. By 1958, at the time of his first solo exhibition at the Leo Castelli Gallery, his work had moved from abstract painting to drawings like “Erased De Kooning” (1953) (which was exactly as it sounds) to what he termed “combines.” These combines (meant to express both the finding and forming of combinations in three-dimensional collage) cemented his place in art history.

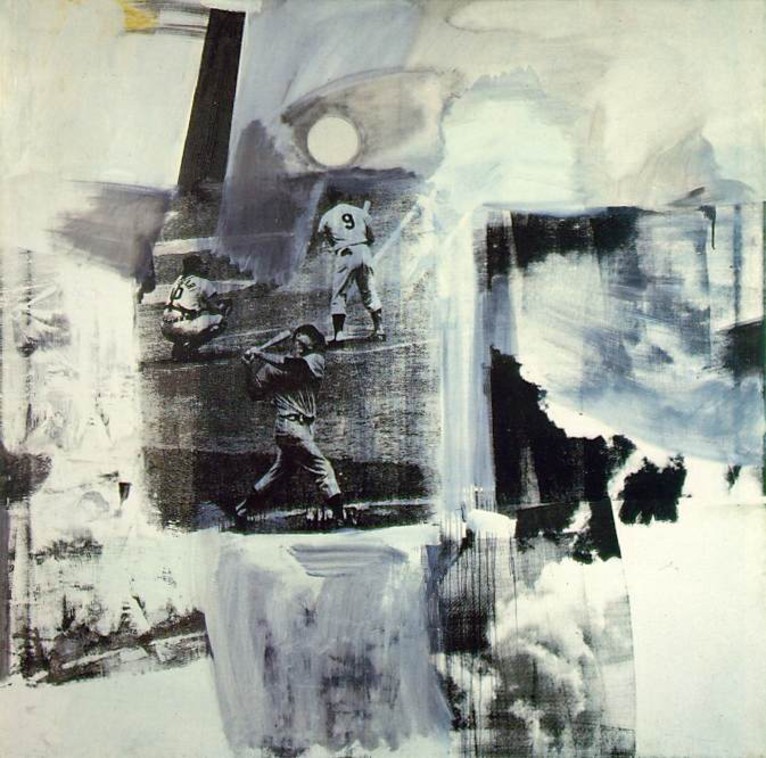

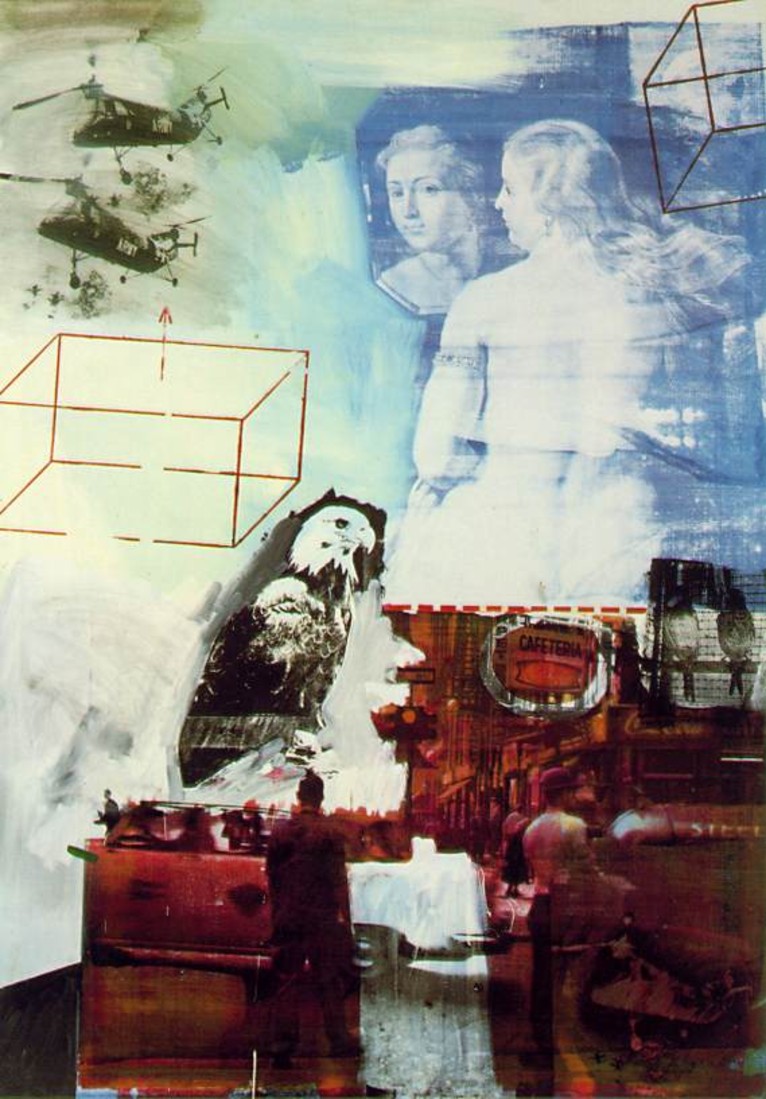

One of Rauschenberg’s first and most famous combines was entitled “Monogram” (1959) and consisted of an unlikely set of materials: a stuffed angora goat, a tire, a police barrier, the heel of a shoe, a tennis ball, and paint. This pioneering altered the course of modern art. The idea of combining and of noticing combinations of objects and images has remained at the core of Rauschenberg’s work. As Pop Art emerged in the ’60s, Rauschenberg turned away from three-dimensional combines and began to work in two dimensions, using magazine photographs of current events to create silk-screen prints. Rauschenberg transferred prints of familiar images, such as JFK or baseball games, to canvases and overlapped them with painted brushstrokes. They looked like abstractions from a distance, but up close the images related to each other, as if in conversation. These collages were a way of bringing together the inventiveness of his combines with his love for painting. Using this new method he found he could make a commentary on contemporary society using the very images that helped to create that society.

One of Rauschenberg’s first and most famous combines was entitled “Monogram” (1959) and consisted of an unlikely set of materials: a stuffed angora goat, a tire, a police barrier, the heel of a shoe, a tennis ball, and paint. This pioneering altered the course of modern art. The idea of combining and of noticing combinations of objects and images has remained at the core of Rauschenberg’s work. As Pop Art emerged in the ’60s, Rauschenberg turned away from three-dimensional combines and began to work in two dimensions, using magazine photographs of current events to create silk-screen prints. Rauschenberg transferred prints of familiar images, such as JFK or baseball games, to canvases and overlapped them with painted brushstrokes. They looked like abstractions from a distance, but up close the images related to each other, as if in conversation. These collages were a way of bringing together the inventiveness of his combines with his love for painting. Using this new method he found he could make a commentary on contemporary society using the very images that helped to create that society.

From the mid sixties through the seventies he continued the experimentation in prints by printing onto aluminum, moving plexiglass disks, clothes, and other surfaces. He challenged the view of the artist as auteur by assembling engineers to help in the production of pieces technologically designed to incorporate the viewer as an active participant in the work. He also created performance pieces centered around chance. To watch dancers on roller-skates (”Pelican”, 1963) or to hear the sound of a gong every time a tennis ball was hit (”Open Score”, 1966), was to witness an art that exchanged lofty ambitions for a sense of excitement and playfulness while retaining meaning.

Throughout the ’80s and ’90s Rauschenberg continued his experimentation, concentrating primarily on collage and new ways to transfer photographs. In 1998 The Guggenheim Museum put on its largest exhibition ever with four hundred works by Rauschenberg, showcasing the breadth and beauty of his work, and its influence over the second half of the century. Rauschenberg lives in Florida and continues to work, bringing his sense of excitement and challenge into a new century.

Throughout the ’80s and ’90s Rauschenberg continued his experimentation, concentrating primarily on collage and new ways to transfer photographs. In 1998 The Guggenheim Museum put on its largest exhibition ever with four hundred works by Rauschenberg, showcasing the breadth and beauty of his work, and its influence over the second half of the century. Rauschenberg lives in Florida and continues to work, bringing his sense of excitement and challenge into a new century.